In the Brownfields redevelopment world, there’s number of keywords and acronyms used throughout the process–from the planning stage to ribbon-cutting stage. We’ve compiled an extensive glossary of commonly used words, so that you can know the industry lingo and can be a Brownfields redevelopment pro.

Use the links below to navigate throughout the page.

All Appropriate Inquiry (AAI) – A process of evaluating the historic and current usage and environmental conditions of a property to assess potential liability. This is usually completed during the purchase or sale of a property.

Abandonment – This happens when a property owner suddenly stops using the property, leaves it vacant, and doesn’t sell it or give it to anyone to resume use.

“As is” Sale – The transfer of a property to a buyer with no promises, assurances, or representations by the property owner about the conditions of the property.

Aboveground Storage Tank (AST) – A tank that commonly stores chemicals like petroleum and is subjected to strict spill prevention regulations due to the potential danger of its contents to affect human health and the environment.

Activity and Use Limitation (AUL) – This institutional control is intended to reduce the time a human comes into contact with a contamination by putting restrictions on how the contaminated property can be reused.

Brownfields Advisory Committee (BAC) – This is a group of stakeholders, including members of the municipality, the community, and the developers who work to provide grant funding to Brownfields redevelopment sites in their area.

Bluefields – Real estate term to describe a property that is either itself a body of water, or is directly adjacent to a body of water.

Bona Fide Prospective Purchaser (BFPP) – A landowner that knowingly or has reason to know purchases a contaminated property and through the process of the environmental due diligence process (Phase I ESAs, etc.) can establish liability protection from being responsible for the contamination. A very stringent set of steps are required to establish BFPP status and there are ongoing requirements to maintain this status even after environmental cleanup is complete.

Brownfield – An industrial or commercial property that is either abandoned, unused, or underused due in part to the presence or perceived presence of environmental contamination.

Certificate of Completion – This is written verification from a state regulatory agency stating the site has been remediated to satisfactory standards. In some states, this certificate provides the property owner with protection from being sued; however, in most states, a property owner will need to obtain a covenant not to sue to protect them from legal liability.

Cleanup Approval Letter – See Certificate of Completion

Clean Water Act (CWA) – This law was enacted in 1972 and regulates the amount of pollutants permitted to be discharged into US waterways.

Community Advisory Group (CAG) – A group of people who live in or close to a Superfund site and are involved in decisions regarding the cleanup. See Superfund Site

Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) – A type of grant that provides money and other resources to address a variety of community development needs, including upgrading building facades, creating public spaces, and addressing infrastructure needs. The CDBG is one of the longest running programs at the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Comfort Letter – A letter issued by the state regulatory agency to a property owner who is affected by, but is not responsible for environmental contamination on their property. The letter establishes liability protection for the property owner. This letter does not typically provide protection from legal suits.

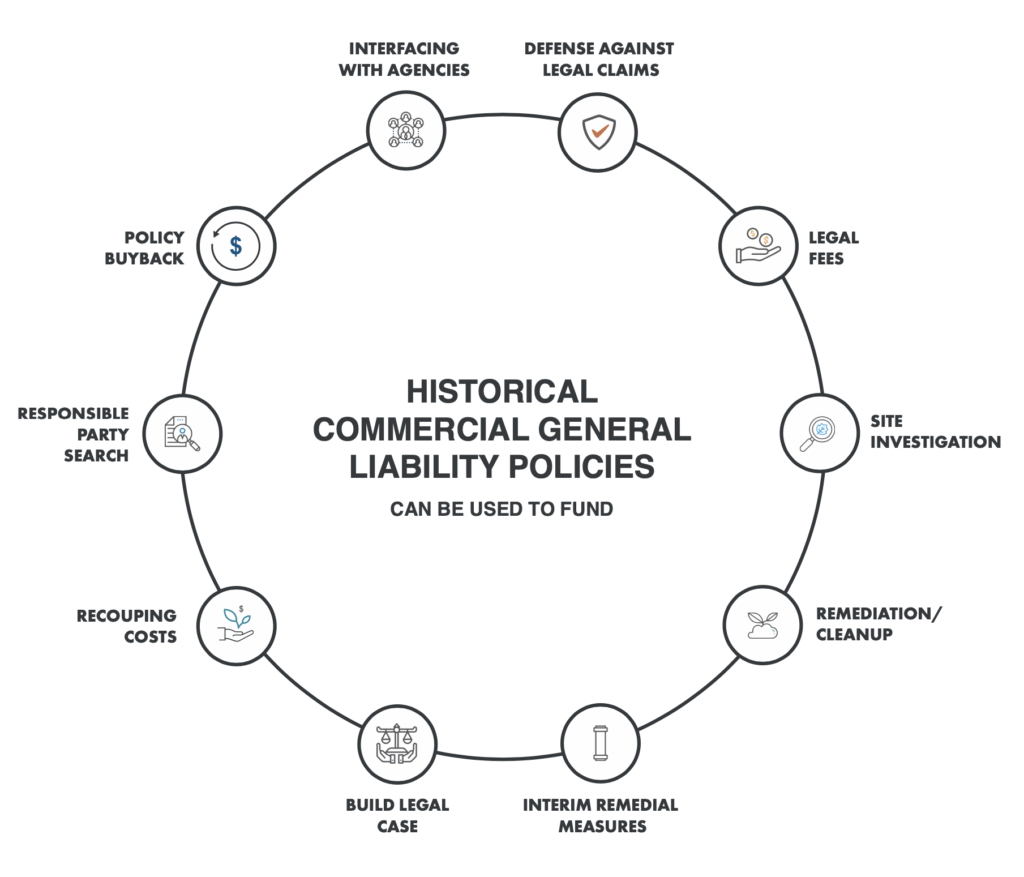

Commercial General Liability (CGL) Insurance Policy – This insurance policy provides coverage to businesses and can defend and indemnify policyholders against claims, such as environmental property damage claims, product liability claims, and claims against employees. See how Commercial General Liability (CGL) Insurance policies work.

Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) – This Act provides federal funding to state or local agencies to clean up large contaminations in particular areas. It also empowers the EPA to seek out Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs) and assure their cooperation in the cleanup. Notifications from the EPA under CERCLA can trigger an insurance carrier’s duty to defend.

Confidential Insurance Archeology® – This is a service provided by PolicyFind, a division of EnviroForensics, that restores financial viability to contaminated properties by conducting searches for historical insurance that may cover costs associated with contamination. See Historical Insurance

Contaminated Media Management Plan (CMMP) – This documentation, prepared by an environmental consultant, provides information needed to identify and properly manage impacted media at a particular site.

Contaminant of Emerging Concern (CEC) – This is a chemical that may cause harm to human health, but effects are not fully understood yet. The EPA typically takes the lead on the evaluation of these chemicals to establish cleanup levels if necessary.

Community Development Corporations (CDCs) – These are local non-profit groups that work to promote and advocate for urban redevelopment projects.

Eminent Domain Condemnation – This is a legal process that allows the government to acquire the title of a property in order to do something with it for the public good. Condemnation can lead to demolition, environmental cleanup, or a number of other solutions that move the property closer to reuse.

Contractor Certification – This process ensures that contractors meet a certain set of standards and are approved to perform specific tasks.

Contractor-Certified Cleanup – When a state allows private contractors to make cleanup decisions on behalf of the state. Only a small number of states have this cleanup process in place as of June 2018.

Contribution Action – When the person or persons identified to be responsible for a contamination take legal action against other liable parties to pay for their share of an environmental cleanup.

Corrective Action – This is the process used to clean up contamination at hazardous chemical treatment, storage, and disposal facilities. This is regulated under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA).

Covenant Not to Sue – This is a written promise by a state government that it will not sue or require further cleanup efforts from a party that has satisfactorily cleaned up their property under a state Brownfields or voluntary cleanup program.

Deed Restriction – This puts limitations on how a property can be used. It appears on the deed to the property.

Due Diligence – This is a thorough evaluation of the environmental conditions of a property. Banks require this during a real estate transaction to ensure they are protected from taking on the liability of a potential existing environmental issue.

Easement – This is the right to use or limit the use of someone else’s property.

Emergency Planning and Community Right to Know Act (EPCRA) – This act requires companies that handle hazardous chemicals to have contingency plans for emergencies, and increases public access to information about chemicals at individual facilities

Engineering Controls – These are physical barriers that are put in place to prevent people from coming in contact with a contamination. Examples: Fences, pavement, clay caps on contaminated soil.

Enforcement of Compliance History Online (ECHO) – This is a directory managed by the EPA that provides compliance monitoring, enforcement, and demographic data on thousands of actively regulated sites across the country.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) – Federal agency responsible for the protection of human health and the environment.

Environmental Assessment – A site investigation conducted to determine the extent, if any, of contamination on a property. They consist of two stages, including Phase I and Phase II.

Environmental Insurance – This is a type of insurance that a person can buy to protect themselves from the financial costs that can come from a lawsuit related to an environmental issue on their property.

Environmental Liability – A probable, measurable, and reasonably estimable future expenditure of resources for environmental investigation and cleanup costs resulting from past transactions or events.

Environmental Remediation – This step in the environmental clean-up process removes pollution or contaminants from soil, groundwater, sediment, and/or surface water.

Exaction – When a local government asks a developer for payment or some sort of concession on a project that serves the public good, like the construction of a sidewalk on land that will be developed.

Foreclosure – This happens when a mortgage lender takes possession of a property because the borrower can’t keep up with their payments.

Feasibility Study (FS) – This is a summary of a site’s contamination, remediation recommendations, and potential reuse.

Greenfield – A property that has no previous development, and therefore does not have an institutional restrictions placed on it.

Heating Oil Tank (HOT) – This is either an aboveground storage tank (AST) or an underground storage tank (UST) that stores oil that powers the furnace of a home.

Hazardous Substance Data Bank (HSDB) – This is a database of chemicals that can cause harm to human health.

Hard Costs – In a construction project, these are the costs associated with the physical construction of the building and any equipment that is fixed.

Historical Insurance – This is a former policy or evidence of a former policy. See Commercial General Liability (CGL) Insurance Policy

Hot Spots – Specific areas at a project site where the level of contamination is very high.

Indemnification – What a commercial general liability policy does for its policyholder. It’s an agreement between the insurance carrier and the policyholder that the carrier will bear the costs for damages or losses incurred by the policyholder.

Independent Cleanup Program (ICP) – A state regulated program where the consultant provides oversight and certification of the cleanup of environmental contamination to expedite the process. This type of program is not available in all states.

Integrated Data for Enforcement Analysis (IDEA) – The environmental performance data for EPA-regulated sites.

Infill Development – The process of developing a vacant parcel in an urban setting surrounded by development.

Infrastructure – The streets, sidewalks, electrical and water utilities, and other public amenities that allow a society to function

Institutional Controls – The legal restriction put in place to reduce human interaction with an existing chemical contamination by limiting the use of a property. Examples include: Deed Restrictions, Easements, Warning Signs and Notices, and Zoning Restrictions.

Insurance Archeologist – An expert at identifying and locating lost liability insurance policies and assets that can be used to defend or indemnify policyholders against claims.

Insurance Archeology – The practice of retracing historical insurance coverage to identify past owners and operators of companies. See Historical Insurance

Insurer – The person or entity that enters into an agreement with a policyholder to protect the policyholder from potential expenses associated with injury.

Land Disposal Restrictions (LDR) – An EPA program that sets guidelines treating hazardous waste order for it to be safe enough to discard in a landfill.

Landowner Liability Protection (LLP) – Legal protections for people who own Brownfields properties.

Liability Relief or Liability Release – This is an official document that prohibits a lawsuit against a company responsible for environmental contamination. This order can be used as an incentive to compel the responsible party to clean up the contamination. Examples include: Covenant Not to Sue, No Further Action (NFA) Letter

Long-term Stewardship – This is a long-term view for environmental remediation on sites, which brings financial and environmental stewardship into the remediation planning stages.

Maximum Allowable Soil Concentration – Standard for the highest concentration of heavy metals in soil that’s still safe for human exposure.

Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) – The maximum amount of a contaminant allowed in public drinking water as set by the EPA and regulated by the Clean Drinking Water Act.

Monitoring Well (MW) – This is a hole in the ground from which environmental professionals can collect groundwater samples.

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) – This is a program under the Clean Drinking Water Act that regulates chemical discharges from the source area.

National Priorities List (NPL) – This is the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) list of the most serious hazardous chemical releases. It’s a guide for the agency to determine which sites need further investigation and more resources dedicated to address the contamination.

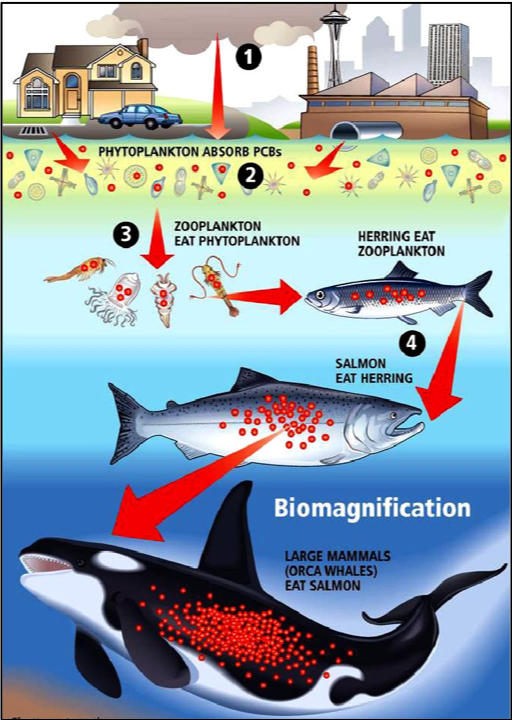

Natural Resource Damages – This is contamination that causes harm to any natural resource including land, fish, wildlife, air, water, groundwater, drinking water supplies, and other resources.

No-Further-Action (NFA) Letter – This is a letter from a state regulatory agency that says it will not pursue any further legal action against a party because that party has satisfactorily cleaned up their property.

No Further Remedial Action Planned (NFRAP) – This is a declaration from the EPA that no further remediation efforts are needed at a site under CERCLA.

Notice of Violation (NOV) – This is a notice that informs the recipient that the EPA believes they have committe one or more violations, and directs them work towards compliance.

Nonresidential Use Standard – This is the amount of a chemical that is considered safe for human exposure at a nonresidential property. Nonresidential standards tend to be more relaxed because people are only inhabiting these buildings for a small portion of the day during business hours.

Oil Pollution Act of 1990 (OPA) – A law that works to prevent oil spills by enforcing the removal of the oil from the contamination site and assigning liability to the responsible party.

Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation (OSRTI) – This is the office at the EPA that manages the Superfund program.

Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response (OSWER) – This office provides policy, guidance and direction for the EPA’s emergency response and waste programs.

Office of Underground Storage Tanks (OUST) – Office at the EPA that manages the guidance and direction for oversight of Underground Storage Tanks.

Preliminary Assessment (PA) – A very elementary review of a known or suspected contamination site.

Phase I Environmental Site Assessment (ESA) – A site investigation conducted by an Environmental Professional to learn the current and past history of a property, and determine the possibility of a Recognized Environmental Condition (REC).

Phase II ESA – If it is determined that a REC may be present on a property, a Phase II Environmental Assessment is recommended. This involves soil and groundwater sampling at the property to confirm the presence of contamination.

Policyholder – Person or entity that enters into an agreement with the insurer that says the insurer will protect the policyholder from expenses associated with injury.

Potentially Responsible Party (PRP) – People, companies, or any other organizations that may be responsible for a chemical release at a Superfund site, and may be liable to pay for cleanup costs.

Preliminary Assessment (PA) – This is a very elementary review of a known or suspected contamination site.

Preliminary Remediation Goal (PRG) – Goal to bring concentration of a chemical down to the point that any residual impacts will be within an established standard of acceptability.

Tetrachloroethylene (PERC or PCE) – This is a manufactured chemical commonly used in dry cleaning and in degreasing mechanical equipment.

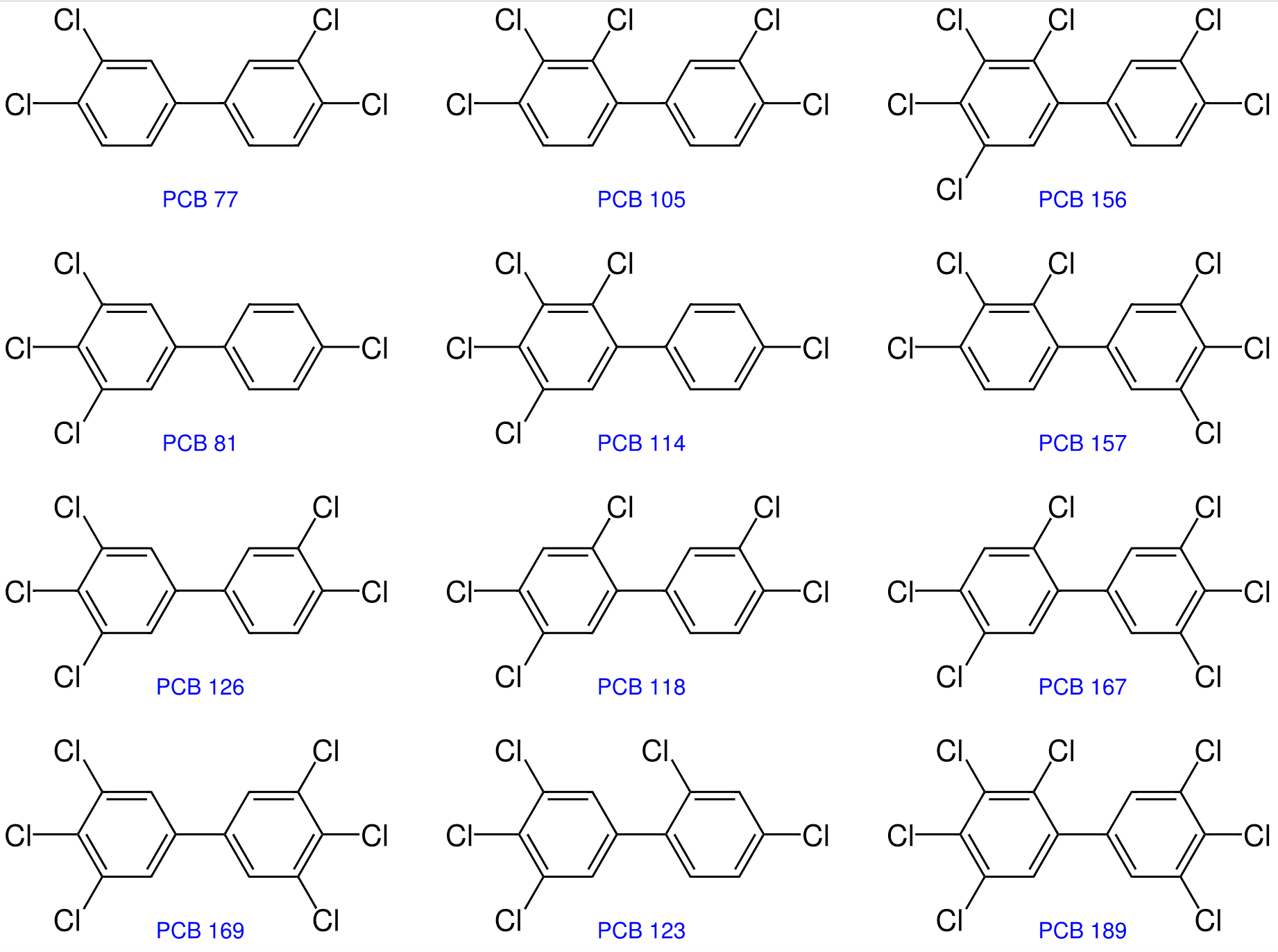

Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) – A toxic chemical that was once used to insulate electrical transformers, capacitors, and other utility lines. The use of PCB was banned in 1979.

Potential Responsible Party (PRP) – These are the individuals, companies, and organizations that may be responsible for a chemical contamination, and may be compelled to pay for cleanup efforts.

Pro Forma – In a real estate project, this is a carefully calculated estimate of the financial return that proposed real estate project is likely to generate.

Prospective Purchaser Agreement (PPA) – This is an agreement between the government and a prospective buyer of a Superfund site that protects the prospective buyer from certain liabilities for contamination that is already on the site. This agreement normally comes with a promise from prospective buyer to provide something of substantial public benefit.

Quality Assurance Project Plan (QAPP) – This is an outline written up during the due diligence and environmental cleanup process that states the project objectives and monitoring parameters.

Remedial Action (RA) – This phrase encompasses all efforts to clean up a site including the construction of systems and/or in situ exercises.

Remedial Action Operation (RAO) – Any operation, maintenance, or monitoring in support of the Remediation Action.

Risk Based Corrective Action (RBCA) – The strategy of cleaning up based on the risk to human health and pushing towards closure using appropriate levels of action and oversight.

Reopener Provisions – These agreements allow the government the right to require further cleanup if a previously unknown contamination is discovered or the remaining contamination is more toxic than originally believed.

Representations and Warranties – Representations are the basic underlying facts in contract law. The Warranties are the promises that a seller makes to a buyer assuring the factuality of the representations about the good being sold.

Request-for-Proposals (RFPs) – This is a document that is put out by a state agency asking developers for their qualifications and credentials and as well as project-specific plans.

Residential Use Standard – This is the amount of a chemical that is considered safe for human exposure in a residential building. Residential standards are the strictest use standards, and if a property passes these standards it can typically be reused for any purpose.

Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) – This Act regulates the generation, transportation, storage, treatment and disposal of hazardous waste.

Restrictive Covenant – A specific type of deed restriction that prohibits the use certain parts of a property to reduce human exposure to existing contamination.

Risk Assessment – An evaluation of a property that identifies the potential harm an existing contamination will have on human health.

Running With the Land – The rights and obligations attached to the land that remain the same regardless of ownership.

Site Investigation – The practice of sampling soil, groundwater, to determine the presence and extent of a chemical contamination.

Site Status Letter – A letter issued by the state regulatory agency to a party responsible for an environmental cleanup that the levels of contamination substantially meet screening levels and that the agency does not anticipate enforcement action against the responsible party.

Soft Costs – In a construction project, these are the costs associated with project planning, including architectural, engineering, administrative, legal, and design activities.

Superfund – Formally known as CERCLA, this fund was established by the US EPA to pay for large, long-term cleanup projects. The parties responsible for the contamination are ultimately required to either cleanup the contamination or reimburse the government for EPA-led cleanup work.

Tax Increment Financing (TIF) – This allows local governments to use future projected tax revenue to finance current infrastructure projects.

Tax Credits – This is an incentive for a large corporation to develop in a local municipality in exchange for a break on their property taxes.

Toxic Tort Action – A lawsuit brought against a company that seeks damages for an exposure to a hazardous substance.

Uncertainty Premium – The amount a buyer subtracts from the purchase price to reflect the risk of unexpected environmental assessment and cleanup costs.

Use Permit – A type of variance that authorizes an otherwise unacceptable use on a property without changing its zoning.

Variance – This is a mechanism that allows a property owner to use their property for something other than what the zoning ordinance permits.

Voluntary Cleanups – Cleanups of identified contamination that are not court or agency ordered. Most states have voluntary programs that encourage voluntary cleanups and that may provide benefits if volunteers meet specified standards.

It’s estimated that there are over 450,000 Brownfields across the United States, and while Brownfields redevelopment can be a lengthy and complex process, with the right team you can speed up the process and stay on track by turning environmental liabilities into assets®.

Contact us today.

Mr. R. Scott Powell is a Senior Project Manager with over 20 years of environmental consulting experience. Mr. Powell’s expertise covers a wide variety of projects ranging from due diligence, LUST/petroleum, hazardous material remediation, asbestos, lead-based paint, remedial actions, to remedial systems. He manages complex relationships fostering the cohesive involvement of several parties on multiple sites with co-mingled contaminant plumes requiring the implementation of remedial solutions for chlorinated solvents, hazardous materials, and petroleum hydrocarbon impacts. He has extensive experience with environmental regulatory compliance, including Clean Water Act (CWA), Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation Liability Act (CERCLA), Resource Conservation Recovery Act (RCRA), Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA), and Toxic Substance Control Act (TSCA). Mr. Powell manages negotiations with state and federal regulatory agencies, provides litigation support in matters concerning environmental issues, and acts as a third-party reviewer of work performed by others.

Mr. R. Scott Powell is a Senior Project Manager with over 20 years of environmental consulting experience. Mr. Powell’s expertise covers a wide variety of projects ranging from due diligence, LUST/petroleum, hazardous material remediation, asbestos, lead-based paint, remedial actions, to remedial systems. He manages complex relationships fostering the cohesive involvement of several parties on multiple sites with co-mingled contaminant plumes requiring the implementation of remedial solutions for chlorinated solvents, hazardous materials, and petroleum hydrocarbon impacts. He has extensive experience with environmental regulatory compliance, including Clean Water Act (CWA), Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation Liability Act (CERCLA), Resource Conservation Recovery Act (RCRA), Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA), and Toxic Substance Control Act (TSCA). Mr. Powell manages negotiations with state and federal regulatory agencies, provides litigation support in matters concerning environmental issues, and acts as a third-party reviewer of work performed by others.

2. Willard Carpenter House

2. Willard Carpenter House 3. Pearl Laundry

3. Pearl Laundry

6. Indianapolis Central Library

6. Indianapolis Central Library  7. Hirschman-Bryan House

7. Hirschman-Bryan House 8. Indiana University Auditorium

8. Indiana University Auditorium 9. Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument

9. Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument 10. Gary Aquatorium

10. Gary Aquatorium

Local Government Agencies

Local Government Agencies

Community and Neighborhood Groups

Community and Neighborhood Groups Lenders and Financial Groups

Lenders and Financial Groups Developers

Developers Environmental Consultants

Environmental Consultants