BY: CASEY MCFALL, CHMM, AND DELANIE BREUER

A change is coming to the environmental due diligence world, which is anticipated to play a factor in how recognized environmental conditions (RECs) (i.e., known or potential environmental concerns) are identified in future Phase I Environmental Site Assessments (ESAs). The change is the potential designation of at least two per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a “hazardous substance” under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as Superfund.

Most people, may not be aware of how this designation could dramatically alter Phase I ESA conclusions or significantly impact future commercial real estate due diligence. To assist with understanding the potential impacts of this designation, below are some of the frequently asked questions we’ve received from brokers, real estate agents, property owners, prospective purchasers and financial institutions regarding PFAS and its anticipated CERCLA designation.

WHAT ARE ENVIRONMENTAL DUE DILIGENCE AND PHASE I ESAS?

Often, prospective purchasers and financial lenders, will want a Phase I ESA completed for a property prior to the acquisition or finalizing lending. Completing a Phase I ESA correctly prior to a property purchase affords the purchaser some protection from liability for environmental contamination existing on the property prior to the purchase.

Very simply, a Phase I ESA is a commercial environmental assessment; the purpose is to identify known or potential environmental concerns for a property based on historical and current operations and nearby neighboring operations so they can be considered when negotiating and finalizing the transaction. Samples are not generally collected during a Phase I ESA: records are reviewed, a property visit is completed, and a determination is made on whether RECs exist on a property. Depending on the findings of the Phase I ESA, a Phase II ESA, (collecting environmental samples), may follow a Phase I ESA.

WHAT ARE PFAS AND WHY ARE THEY AN ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERN?

PFAS are a group of 9,000 or more chemicals that were first developed in the 1930s and are widely used in everyday products, including as the main ingredients in developing water-resistant chemicals textiles and paper products, nonstick coatings, and cleaning products. PFAS are also prevalent in aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), which is used to suppress particularly volatile fires primarily by municipalities, airports and maritime fire departments. Electronic manufacturing and electroplating operations also used PFAS in their operations.

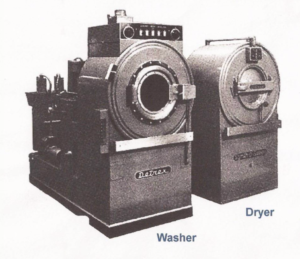

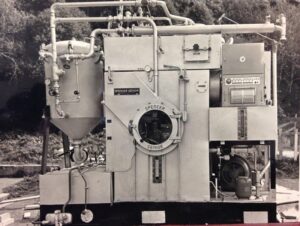

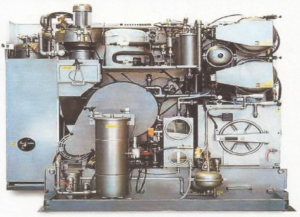

Historically, PFAS have also been found in many widely used items such as shampoo and cosmetics, non-stick cookware, stain-resistant or waterproofing products, fast food packaging, paints, and pesticides. Biosolids from sewer treatment plants, which can be used as fertilizer for farm fields, can also contain PFAS from the upstream sources that discharge to the municipal sewer system (i.e., personal machines or commercial laundry services used to wash “waterproof” clothing, industrial facilities that use PFAS chemical, etc.).

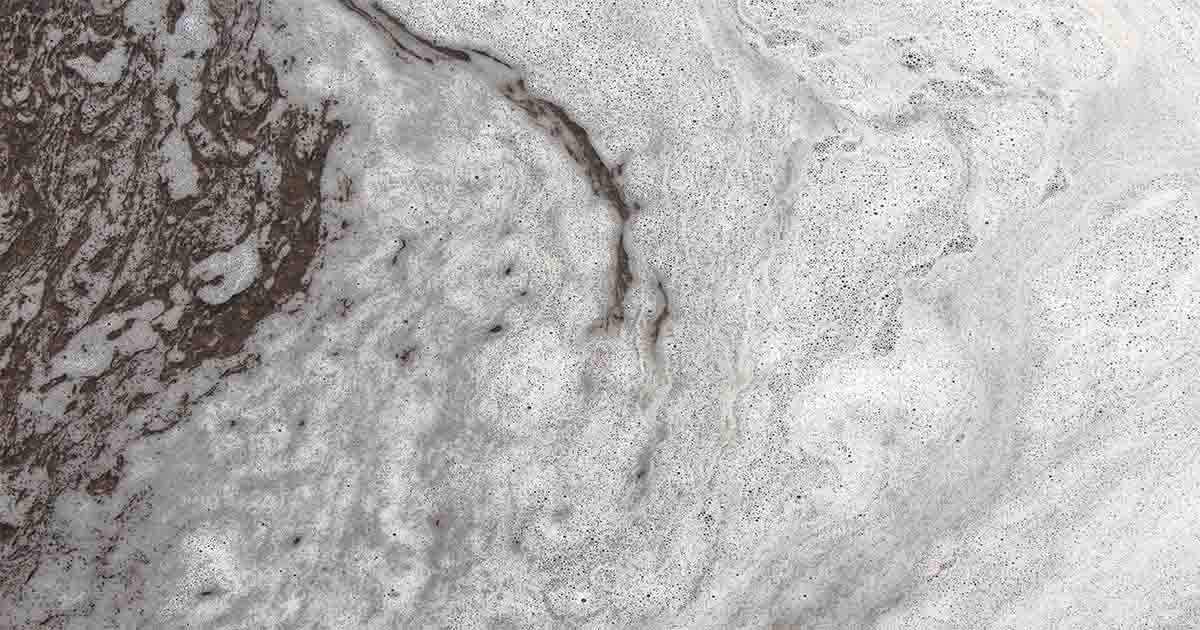

A PFAS compound can be identified by its carbon-fluorine bond, which is exceptionally strong and gives the compounds many of their useful properties. However, this also means PFAS substances are slow to break down in the environment. PFAS easily travel through environmental mediums like groundwater, and some PFAS can bioaccumulate in humans and animals. Though research on these compounds is ongoing, some studies have linked PFAS exposure to health concerns in humans and animals, which prompted the proposed CERCLA designation as a hazardous substance.

As noted, there are over 9,000 PFAS compounds, but the two most widely used and most studied PFAS are Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA).

WHAT DOES THE “HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE” DESIGNATION MEAN AND WHY AREN’T PFAS ALREADY BEING ASSESSED AS PART OF PHASE I ESAS?

A hazardous substance designation means that the federal and state regulators can force environmental investigations and require cleanup or remediation of these substances when they are released to the environment, or some cases, when they are discovered on a property even if it is unknown when or how they were released. All chemicals proposed for hazardous substance designation must undergo a rigorous evaluation prior to designation.

Although PFAS have been around since the 1930s, only recently have scientists made a link between PFAS and their adverse health effects. Specifically, many of the studies have focused on PFOA and PFOS. These two compounds and their salts and isomers were first proposed for hazardous substance designation in September 2022. Currently, it is widely believed that the hazardous substance designation for these PFAS compounds will likely occur within the next 6 to 12 months based on an April 2023 notice from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

When assessing properties for potential contamination through a Phase I ESA, industry standards do not require PFAS to be evaluated because they are not petroleum products or CERCLA-designated hazardous substances. The ASTM standard for preparing Phase I ESAs (ASTM E1527-21) states that only petroleum products or CERCLA-designated hazardous substances must be considered when identifying RECs. PFAS may be considered as an out-of-scope item, the same as asbestos-containing materials (ACM) or lead-based paint, but an assessment is not currently required.

HOW WILL THE PFAS HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCE DESIGNATION AFFECT COMMERCIAL PROPERTY TRANSACTIONS?

Properties that would not previously have had RECs identified in a Phase I may now have an identified REC based on the potential for PFAS contamination. Because PFAS has been so prevalent in manufacturing, and can move freely through the environment, this has the potential to impact many properties.

For example, laundromats that have never housed dry cleaning operations would be unlikely to have a REC identified in a current Phase I ESA. However, studies from Florida have shown that laundromats may have PFAS present from waterproof, or stain resistant coatings being stripped off from laundered clothes. Another pertinent example could involve farms that have applied biosolids from municipal sewer treatment plants as fertilizer on their fields. Studies have shown these biosolids may contain PFAS and have the potential to leach into soil and groundwater, thereby causing a potential environmental issue. Agricultural fields by-and-large have not been an environmental concern in Phase I ESAs, although this could change under the upcoming PFAS hazardous substance designation.

SHOULD I TEST FOR PFAS?

The answer to this question is “it depends.” The variables to be considered include the historical use of the property (i.e., could the operations have caused or contributed to PFAS in the environment); the historical use of nearby properties, from which PFAS could potentially have migrated; whether you own or are purchasing the property; and how the discovery of PFAS may impact you.

For example, in some states, even discovering a small amount of PFAS may trigger reporting and potential remediation requirements, so although a potential buyer may wish to test for PFAS, the seller may be less inclined.

The location of the property, and the applicable state and local regulations, also play a key role. In Indiana, for example, there are not currently requirements for PFAS testing during environmental investigations. However, in Wisconsin, state regulators require an evaluation of potential PFAS on the property. If PFAS is known or suspected to be present, the regulators may require testing, and reporting and potential remediation if any amount of PFAS is discovered on a property, regardless of the source of contamination. The best advice is to consult with your attorney and environmental consultant to determine the risks and benefits of PFAS sampling based on your circumstances.

If and when PFAS are designated as hazardous substance under CERCLA, the choice on whether to sample or not for PFAS will change to a requirement based on REC findings.

The bottom line is that the impending designation of PFAS as a hazardous substance may have far-reaching effects in the environmental world. This, however, does not mean the sky is falling. Property owners and prospective purchasers should be aware of these upcoming regulations and a trusted environmental consultant and attorney can help guide you through the next steps.

EnviroForensics and Fredrikson & Byron have proven track records of helping dry cleaners and laundromats through environmental investigations and cleanup, often while business goes on as usual. In some instances, EnviroForensics may be able to help find historical insurance to fund the investigation and cleanup.

If you have questions regarding PFAS or any other environmental matter, please contact us at your convenience.

Delanie Breuer practices environmental law at Fredrikson & Byron P.A. in Madison, Wisconsin. Ms. Breuer can be reached at 608-453-5135 or via email at dbreuer@fredlaw.com. Casey McFall is the Director of Real Estate Services and a senior scientist for EnviroForensics, LLC. Mr. McFall can be reached at 317-972-7870 or via email at cmcfall@enviroforensics.com.

As seen in Cleaner & Launderer.